The mystical mountain men of Japan

Featuring The Legend of how Japan's most famous mountain man couldn't quite handle it

How Haguro Shugendo fits in

We Yamabushi practice Shugendo, the do 道, path or way, of gaining supernatural powers, gen 験, through ascetic practice shu 修. Put simply, it’s the practical nature of Shugendo that makes Shugendo Shugendo.

In other words, unlike organised religions1 with written doctrines (I don’t consider Shugendo a religion, it’s a do 道), Shugendo emphasises practice in nature to cultivate spiritual power and abilities.

Spiritual power and abilities? Like what?

Oh, teleportation and flight, for example. Then there’s walking on fire, the ability to control Oni demons, and in rare cases, even Kami (big thanks to Gary Luscombe for help on this information).

And that was just the founder!

En no Gyoja, En the Ascetic, was his name2. En no Gyoja is said to be the first to combine the doctrines of Shinto, Esoteric Buddhism (Tendai and Shingon sects), Taoism from China, and ancient Japanese animism or nature worship into one to form Shugendo.

En no Gyoja (probably) did exist. He is mentioned in the Shoku Nihongi (Chronicles of Japan Continued) written in the Heian period (794-1185). He practiced asceticism on Mt. Yamato Katsuragi on the borders of Osaka and Nara Prefectures in the 7th and 8th centuries.

Those special abilities though?

The jury is still out on that.

One thing is for sure though, the Dewa Sanzan like to boast about how their supposed own founder, a fellow named Nojo Taishi3 (contested, believed to be Prince Hachiko?), one-upped the legendary founder of Shugendo himself.

First, this is contested, obviously, but Nojo Taishi apparently came and opened the Dewa Sanzan mountains for ascetic practice a full century or so before En no Gyoja even existed, 593 to be exact. This would make the Dewa Sanzan mountains the oldest place of ascetic practice in Japan, one huge reason it is contested.

And then of course there is:

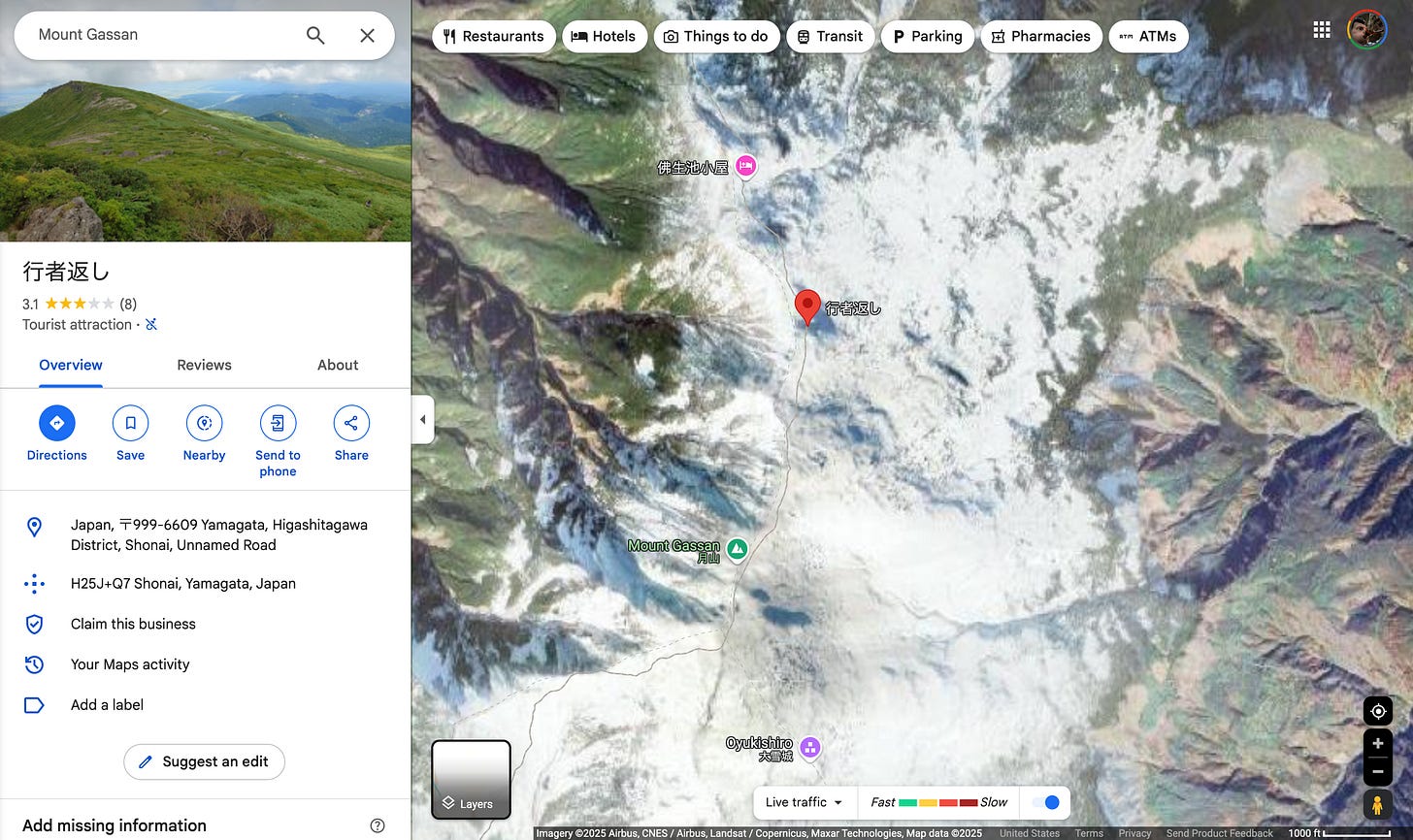

The Legend of Gyoja Gaeshi

The tallest of the three Dewa Sanzan peaks, Gas-san (Mt. Gassan) has a number of famous spots on its slopes. The splendid Midagahara marshlands are said to be home to Amitābha Buddha (Amida Nyorai), the principle deity in Pure Land Buddhism. Or take one of the peaks, Omowashi-yama for example. This name translates to ‘Mt. Give you the Impression’ as it fools you into believing it is the summit, when it is not even close.

‘Mt. Give you the Impression’

And then there is yet another notorious spot on Gas-san called ‘Gyoja Gaeshi’. The more aware of you out there would be able to recognise Gyoja from the aforementioned En no Gyoja, En the ascetic.

Gyoja Gaeshi is named after him.

Apparently.

The ‘gaeshi’ part is from ‘kaesu’, to have someone return. ‘Gyoja Gaeshi’ means ‘where the Gyoja had to turn back’.

The legend of Gyoja Gaeshi goes that when En no Gyoja made it to the notorious spot on Gas-san, he was unable to pass. Because of this one difficult part of the mountain, the all-powerful, all-knowing, all-ascetic En no Gyoja couldn’t even make it. For some reason his superpowers, even that of flight or teleportation, defied him. It wasn’t until En no Gyoja took the teachings of Nojo Taishi on board that he was able to get through and successfully make it up4.

In other words,

Nojo Taishi and Haguro Shugendo was the superior.

Did I mention this was contested?

Anyway, special abilities or not, it was the latter legends and folklore that elevated En no Gyoja to the status of the founder of Shugendo.

Shugendo falls under the category of Mikkyo (Japanese Esoteric Buddhism), itself from an ancient Buddhist practice called 山林仏教 Sanrin Bukkyo, lit. ‘Mountain Forest Buddhism’5. Somewhere along the way a whole lot of other stuff such as Taoism made its way into the mix to create the practice of Shugendo we all know and love.

How did Shugendo spread?

During the medieval period, legends of En no Gyoja’s supernatural abilities spread to areas such as Yoshino and Kumano in current-day Mie, Nara, and Wakayama Prefectures. As a result, Yoshino and Kumano became the two major Shugendo sects in Japan: the Tendai Buddhism Honzan-ha (Head Temple Sect) based at Shogo-in Temple in Kyoto, and the Shingon Buddhism Tozan-ha (Peak Temple Sect) based at Sanbo-in Temple at Daigo-ji in Kyoto.

(Read more about Shugendo here).

And Haguro-san?

As you can probably guess, these weren’t the only places Shugendo thrived. Other regional sacred mountains, such as Haguro-san (Mt. Haguro of Dewa Sanzan in Dewa Province, current-day Yamagata and Akita Prefectures (for the most part), and Hiko-san (Mt. Hiko) on the borders of current-day Fukuoka and Oita Prefectures in Kyushu, also caught wind of En no Gyoja’s supernatural prowess. Wanting a slice of the daikon for themselves, they established their own Shugendo strongholds.

What happened after that?

Up until the Edo period (1603-1868), followers of Shugendo were mainly nomads, wanderers, or dare I say it, vagabonds. Then when the Tokugawa Shogunate took control of Japan they pushed religious policies encouraging more of a permanent existence for followers of Shugendo.

This led to the formation of temple towns near sacred mountain sites, for example the pilgrim’s lodge township of Toge6 at the base of Haguro-san (Mt. Haguro), Japan’s one and only Sangaku Shinko Mountain Worship township still running as originally planned7. Places like Toge meant that commoners too were able to travel to the sacred mountains for their own spiritual benefit, with people coming from primarily eastern Japan.

Which they still do, by the way.

However, the Tokugawa Shogunate weren’t too happy about all these places staking a claim to Shugendo. So, they implemented religious policies that meant only the Honzan-ha and Tozan-ha were recognised as legitimate Shugendo factions. In other words, regional Shugendo groups, such as the Haguro-san and Hiko-san sects, had to affiliate with one of these two factions.

But they were already too late

The Mountain Worship culture had already taken hold in both places by this time. And then it took 50 to 100 years8 for the sects to regain their status as independent centres (Honzan) of regional Shugendo,

but they still did it.

And I for one and extremely thankful they did.

This time was when Haguro, or Toge pilgrim’s lodge township specifically, began an incredible culture of Mountain Worship practices that last to this day, something I discuss here and in the above video.

Basically, when you visit the Dewa Sanzan, stay in a Shukubo pilgrim’s lodge, eat the Shojin Ryori, and get guided by a yamabushi, you are directly contributing to and taking part in a centuries-old tradition,

you become part of the story.

And that, I believe, is something worth celebrating, cherishing, and protecting.

Thanks heaps En no Gyoja! (Or Prince Hachiko?)

Sources:

Dewa Sanzan Sangaku Shinko no Rekishi wo Aruku by Michiaki Iwahana

Daily Yamabushi for This Week

Daily Yamabushi posts for the week of January 17 to 23, 2025.

Read Daily Yamabushi for free at timbunting.com/blog.

My understanding is that Shugendo is a 道 do, a path or way. Officially Shugendo is not a religion as it doesn’t have its own unique doctrines.

The founder of the Dewa Sanzan specifically is contested. Some say the real founder came before En no Gyoja, which would make the Dewa Sanzan Japan’s oldest Shugendo faction (names that come up are Prince Hachiko, Nojo Taishi, and Mifuri-no-Otodo, for example).

Refer to footnote 2.

As above

It’s hard to know what to call Toge. Specifically it is a 地方 region, but really it is a township within the former Haguro Town, now part of Tsuruoka City.

The culture of 講 Ko, group pilgrimages to the mountains led by yamabushi who run the Shukubo pilgrim’s lodges established in the 17th century still continues to this day.

Sorry for the arbitrary number, this is what the book had.